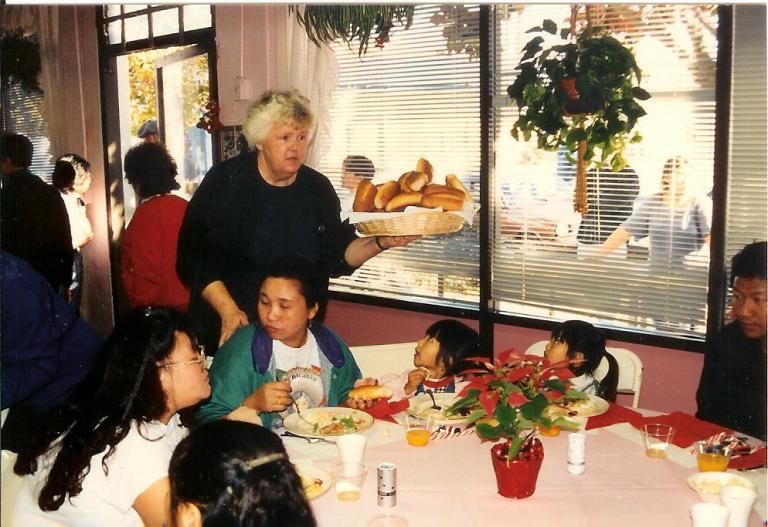

Wellspring Women’s Center is a haven – its dining room painted a rosy pink, peace-bringing paper cranes suspended from its ceiling.

Wellspring Women’s Center is a haven – its dining room painted a rosy pink, peace-bringing paper cranes suspended from its ceiling.

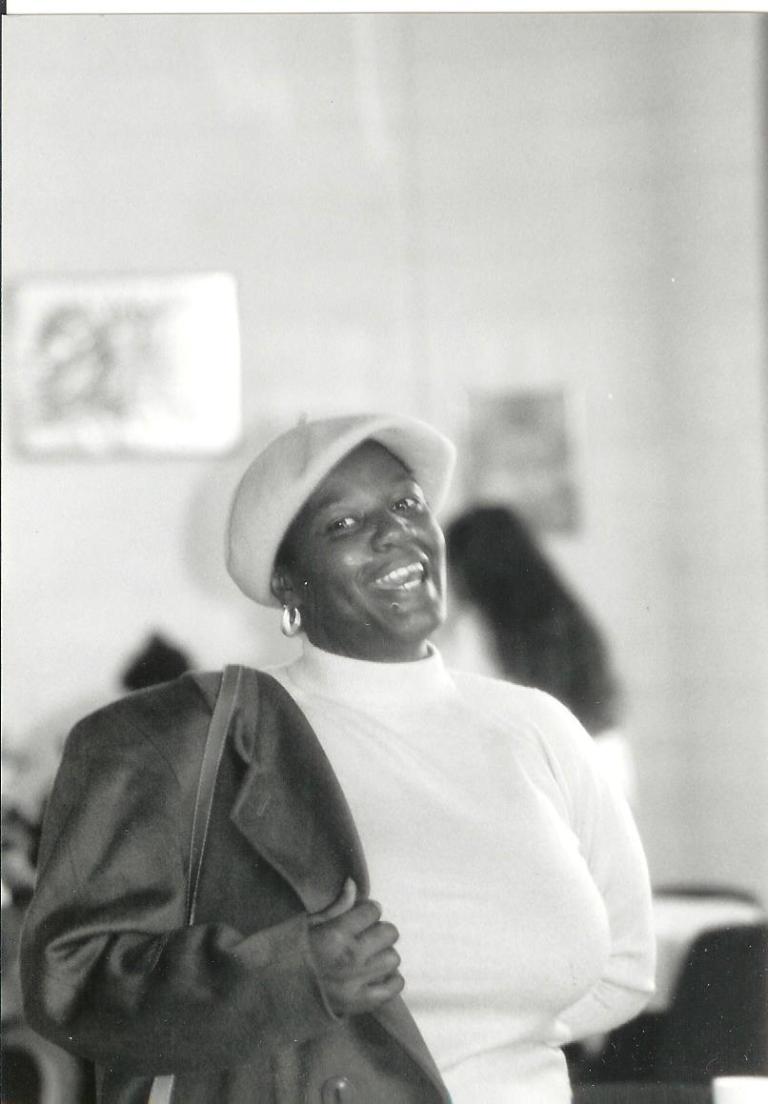

Though smiling faces are abundant, tears, too, are shed here. This is a setting for the magic of radical acceptance.

The women and children who frequent the drop-in breakfast center are referred to as guests and are cherished and honored. They might be low-income, homeless or isolated; but like everyone, they are in need of love.

Some guests see Wellspring as their Starbucks. Others believe it is more magical than Disneyland.

The garage door windows of the former Oak Park firehouse feature seasonal décor. Quilts hang like canopies over the Children’s Corner. The Center has the air of an old woman’s house, furnished with the familial comfort of love spread across generations.

All women and their children are welcome here. Some live in cars. Others are senior citizens living isolated in their homes.

“I come here, because I feel good in here,” said Benigna, staring out the center’s windows onto tree-lined 4th Avenue.

Benigna is a cafeteria worker at Sacramento High School who has been coming to Wellspring for 18 years.

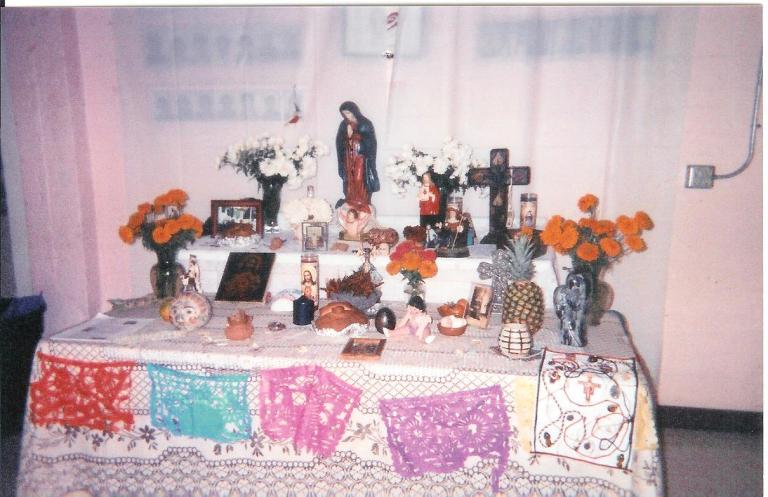

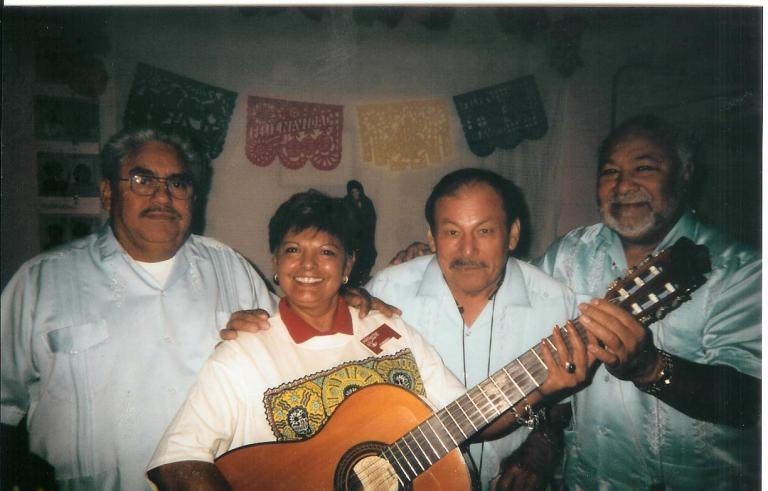

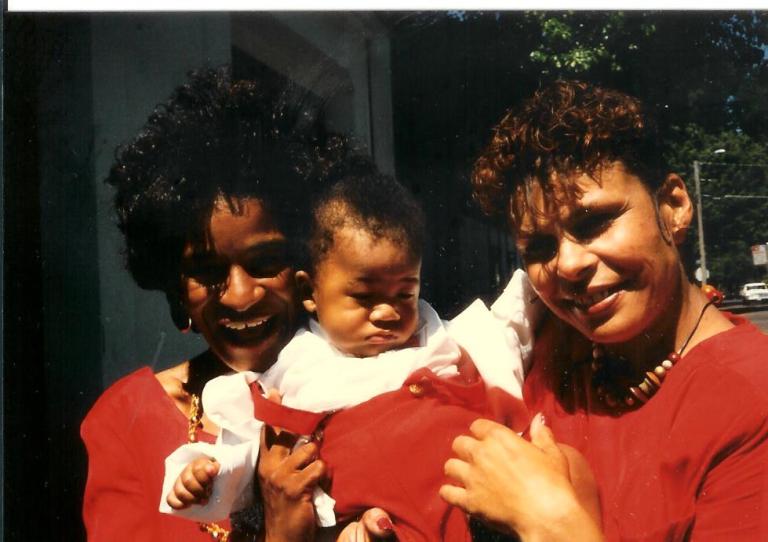

Families have grown up with Wellspring and some guests have been regulars here since it opened over three decades ago. They bring celebrations to the center. Homemade tamales, posole, banana pudding, gorditas, egg rolls, Spanish rice and fried chicken are lovingly shared table to table with guests and staff.

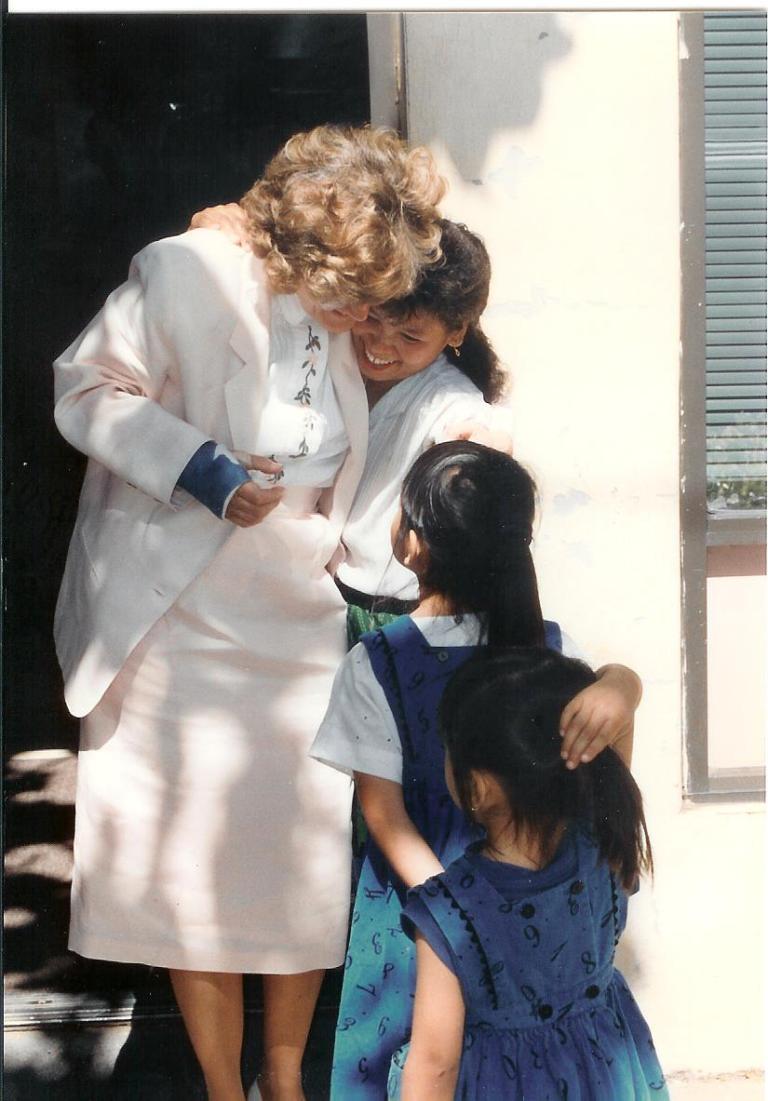

“You will often ask people, ‘Why do you keep coming here for so many years?’” said Sister Judy Illig IBVM , Wellspring’s Executive Director from 2003-2017. “The common answer is ‘You are my family.’”

With a master’s degree in Mathematics Education from Stanford University, she was often caught plunging the center’s toilets and prioritized her time with the guests over her administrative duties. Her hugs seem like blessings.

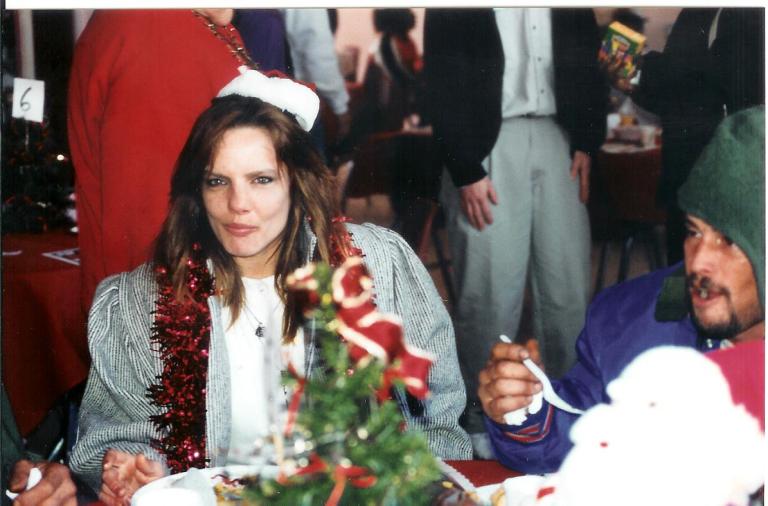

On weekday mornings, Wellspring percolates with cultural, racial and class diversity.

“It’s a party,” said Joyce Weil, a volunteer here since the early 1990s.

“You can’t come here and not feel like you are a part of a community,” said Annie Brackney, Wellspring’s Development Director from 2014-2016. “It’s just what Wellspring is.”

Along with morning coffee, Wellspring serves up cold cereal, oatmeal, yogurt and farmer’s market fruit and vegetables, spa water, coffee and toast to its guests from 7:30 to 11:30 a.m. on weekdays. It also offers social work and chiropractic services, counseling, dance classes, art therapy, haircuts, health and movie screenings, drama therapy, yoga, sewing and wire-working classes and a preschool environment for children between 2 and 8 years old. Wellspring provides some of life’s necessities, including diapers, birthday presents, books, feminine hygiene products, socks, underwear, toiletries, knitting supplies and bus passes.

It also offers social work and chiropractic services, counseling, dance classes, art therapy, haircuts, health and movie screenings, drama therapy, yoga, sewing and wire-working classes and a preschool environment for children between 2 and 8 years old. Wellspring provides some of life’s necessities, including diapers, birthday presents, books, feminine hygiene products, socks, underwear, toiletries, knitting supplies and bus passes.

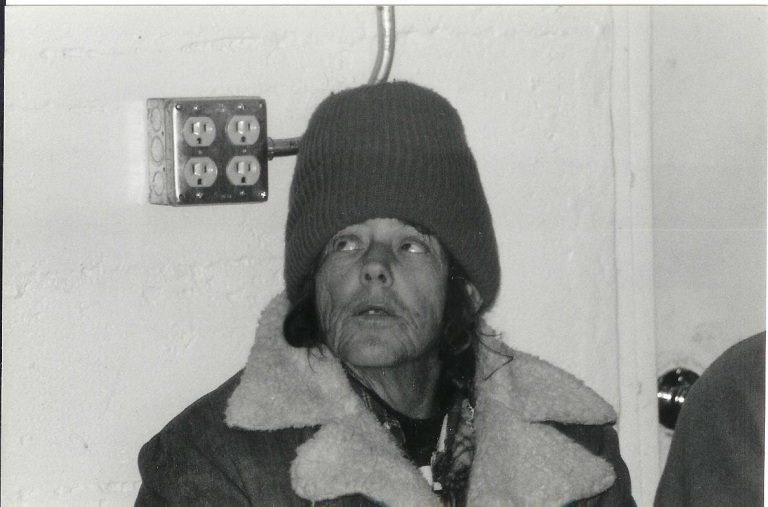

Megan eats her breakfast at Wellspring from time to time. She often eats enough to get through her day. “I like it here because they let me get second helpings of food and I feel welcome here,” she said.

Megan is often homeless. Weathered by the outdoors, dirt and grime have sunk into her skin. She often sits apart from the other guests.

Megan suffers from episodes of psychosis and has been barred from other social service agencies in Sacramento. When she becomes too disruptive at Wellspring, she may be asked to leave. But, she is always welcomed back.

Wellspring might be the only haven for Megan in Sacramento, providing shelter, respite and a meal — a transcendent act of grace in an era of fear and isolation. Wellspring embraces and accommodates differences.

Wellspring embraces and accommodates differences.

“God is good, but Wellspring is better,” said Francine, a guest who started coming to Wellspring 28 years ago when she experienced homelessness.

“It’s hard to describe the way that Wellspring has flourished so well,” said Genelle Smith, Wellspring’s Executive Director. “It is really kind of like that unexplainable way that certain types of plants will grow in the craziest of places and you will just sort of stumble upon them and you’ll wonder, ‘How on Earth did this happen here?’ ”

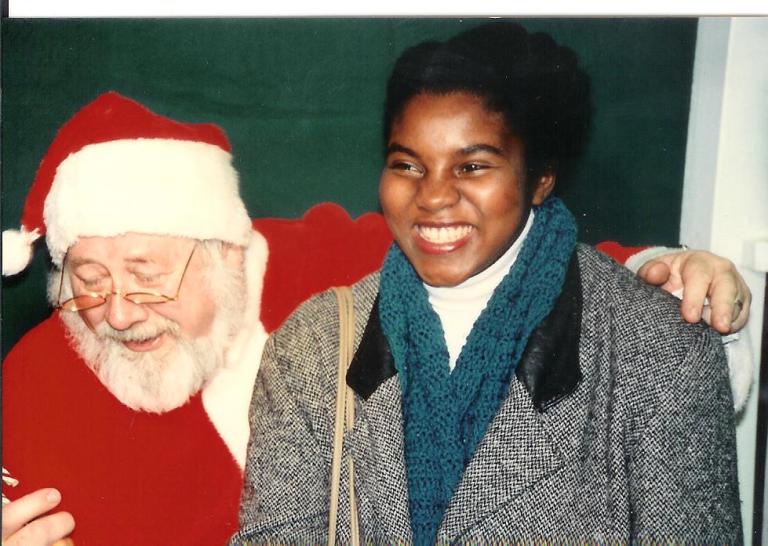

When Sister Catherine Connell and Sister Claire Graham founded Wellspring Women’s Center in 1987, they embarked on a mission to inspire dignity and love in a neighborhood plagued by poverty.

“There was a lot of prostitution and the houses were worn down,” said Sister Claire describing the Oak Park of 1987. “People were isolated. There was no grocery store within miles. The closest store was Safeway on Alhambra Boulevard. There were very few services.”

In 1979, the two Sisters of Social Service met their inspiration for Wellspring while walking in downtown Sacramento. Bedraggled and drunk, a homeless woman named Jean, who they first assumed was a man, tapped Sister Catherine on her shoulder and asked for money.

The three ended up at a nearby Burger King. In exchange for buying her a meal, Sister Claire and Sister Catherine asked Jean to share her story with them.

“There weren’t many homeless women in those days,” Sister Claire said.

Jean, it turned out, attended Sacramento High School during the same time Sister Claire was a student at St. Francis High School. Though contemporaries, Jean suffered from alcoholism and the isolation and fear of living on the streets.

“After we parted ways, I said, ‘Claire, wouldn’t it be wonderful if there was a way that we could offer something more than food and goodbye in the night?’” Sister Catherine recalled.

The two dreamed of their own restaurant-like setting that would serve food and dignity to people in need. The comfort of a cup of coffee, welcoming arms of friendship, grace, and honor would be waiting for women forgotten and demeaned by an unjust world.

“I don’t think people recognized what poverty does,” Sister Claire said. “’An Oak Park activist kept saying to us, ‘We need education, you need to educate my people. If you don’t educate them, they are not going to become much of anything.’ Catherine and I began to realize that when you talk about education, it doesn’t just mean going to school and going to college. It means teaching people from the beginning of their lives to recognize their own worth and their abilities to accomplish things.”

By 1987, Sister Catherine began working toward the dream that would become Wellspring. After resigning from her job as a therapist at Eskaton River Counseling Center, she recruited Sister Claire, who was living in Southern California and working at a summer camp for at-risk youth and those with disabilities.

“Claire agreed and we just plowed into it,” said Sister Catherine.

The community of the Sisters of Social Services agreed to support their living expenses while they were getting Wellspring off the ground.

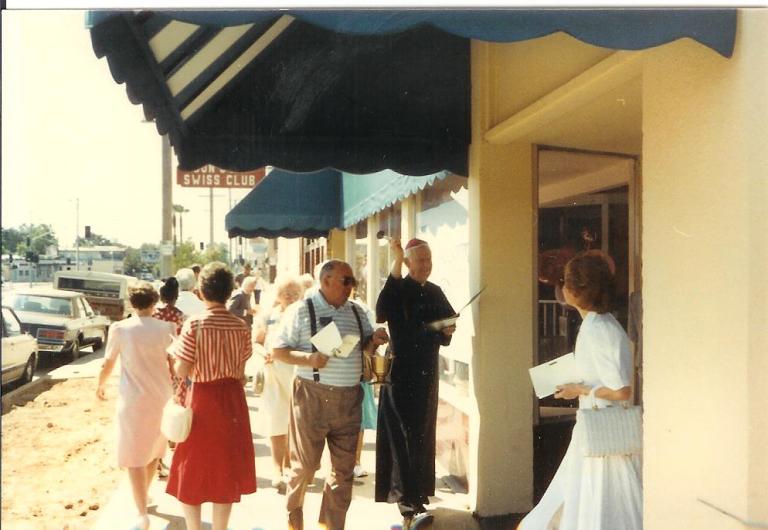

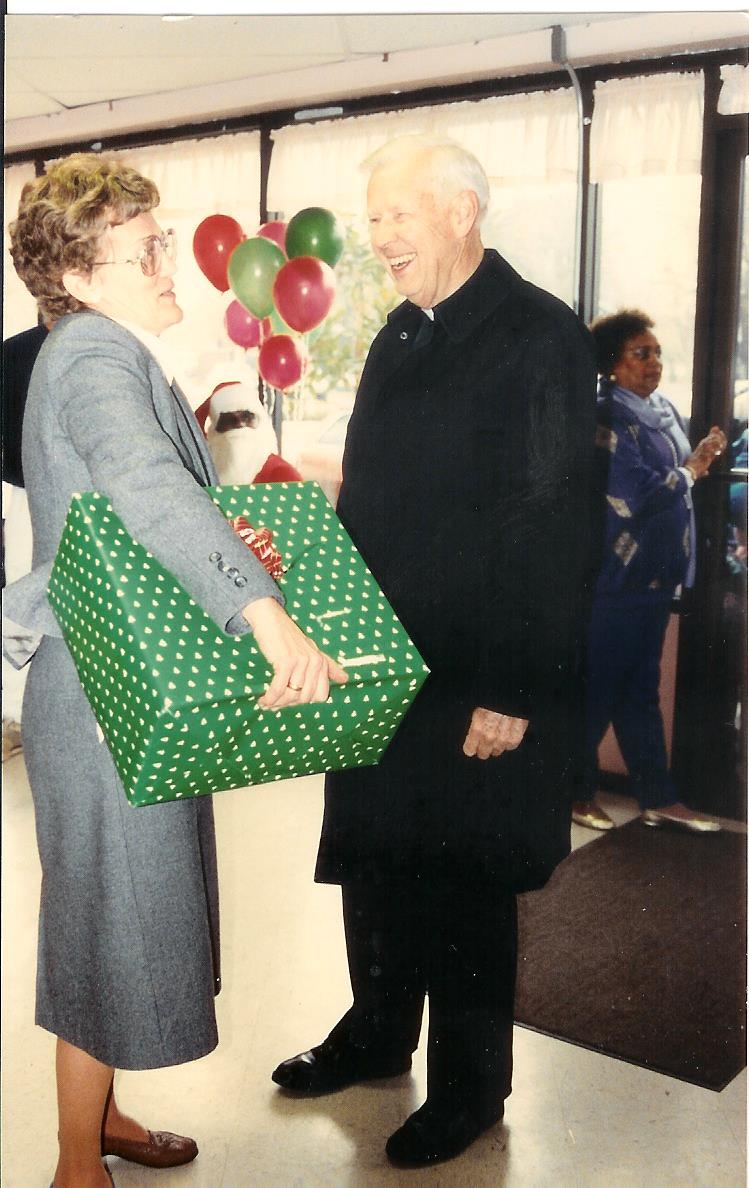

Father Dan Madigan, a leader of the Catholic Diocese in Sacramento and a pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church in Oak Park, found them a house in Oak Park and a storefront at 34th Street and Broadway that rented for $230 a month.

Sister Claire and Sister Catherine visited churches of all religious denominations to drum up support for their new mission.

“We started to invite volunteers and donors to be a part of Wellspring when we spoke at churches and about what we do and about what Wellspring does,” Sister Catherine said. “Some people were inspired by the talks and said, ‘I want to volunteer.’”

Their efforts paid off, with 148 women stepping forward to help launch Wellspring, which was not necessarily greeted with open arms.

At first, Oak Park residents feared the project would siphon off government money promised to the community.

“Politically, we have had some difficulties with neighborhood opposition,” Sister Claire wrote. “This required us to attend meetings, visit neighbors and generally serve as ambassadors to help provide a positive image of our project to the Oak Park community.”

Sister Catherine walked throughout the neighborhood, introducing herself and Wellspring to wary residents, and invited to them to the center for coffee. She also assured them that Wellspring would receive no government funding.

“It was a real learning experience because it gave me a real sense of what it was like to live in the community,” Sister Catherine said.

Wellspring’s first location was noted for its pink tablecloths and a gazebo designed by an architect friend of Sister Catherine’s.

At the breakfast haunt, Sister Catherine and Sister Claire decided to honor every story that their guests told them.

“No one listens to the stories of the poor,” Sister Claire said.

An early flyer for Wellspring read: “Women’s worth is undermined by Oak Park’s reputation.”

An early flyer for Wellspring read: “Women’s worth is undermined by Oak Park’s reputation.”

Many women, Sister Catherine elaborated, are forced to wait at the welfare office for hours for help — a discourtesy that conveys to them that their time is not valuable and that they are not worthy. Their willingness to accept this treatment, she said, reinforces low self-esteem.

“People don’t say that they come to Wellspring because of a meal. … People know that when they come here, they are going to be cared for and that they are going to be heard,” said Annie Brackney.

“Dignity means that when a person is interacting with another person, they can expect certain kinds of treatment from that other person,” added Genelle Smith. “So for me, that is dignity – it is an interaction or an exchange. It is not something that someone just has on their own.”

To Genelle helping the guests of Wellspring means letting them know that they are always welcome at Wellspring.

“It means bearing witness to guests’ challenges and their struggles with open-heartedness and trying to see clearly what they are needing and what they are wanting,” she said. “Trying to convey to them that those needs and wants are important and that they matter – that they haven’t done anything that means that they will be rejected or turned away. That there is a place that they can come and where they can be themselves. That often means that they have worth beyond anything that they can produce and I think that is a challenging piece to convey in a very capitalistic society where people are always given the message that their worth is about what they can produce.”

“When I first walked in, these people did not judge me by the way I looked, dressed or by my situation,” Pam, a guest, said. “They accepted me as I was. They’ve helped me with housing. They’ve helped me feel better. I would come cry on their shoulder. They don’t have to be concerned about my situation, but they are. They don’t have to care about us, but they do. When you come in here, you feel their love.”

Through shared stories and experiences, generations of women have learned at Wellspring that they matter and are worthy.

“The food wasn’t important, the most important thing was the relationship,” Sister Claire said.

“For us it wasn’t a giveaway program,” she said. “It was to build self-esteem in women. In the beginning, we didn’t give away much of anything other than coffee, doughnuts and conversation.”

At Wellspring, volunteers who may never have interacted with low income women began to understand the heartache of poverty by listening to guests’ stories.

Terri Tork, Wellspring’s volunteer coordinator from 2014-2018, was a volunteer before she became a staffer at Wellspring.

“The experience of volunteering was transformative,” she said.

“It just felt great to be helping people,” Terri said. “It also made me more grateful for all of the goodness that I have in my life. I am totally aware that it is good fortune that allowed me to have so many wonderful things in my life. I stopped whining, moaning and groaning about how sad everything was for me. I saw that there were many people who had things that they were dealing with that were much more difficult than the things that I was dealing with and yet, many of them still managed to be happy and have a good outlook on life. That was a very powerful lesson for me.”

Originally, the center was open to all, including men, from 7 a.m. to 11 a.m. weekdays.

But when Sisters Claire and Catherine applied for a special-use permit for the breakfast center, the City Council decided it should focus on women and children only, warning that the presence of men would promote loitering outside of the facility.

“I think it was the Holy Spirit that said, ‘Don’t serve men,’” Sister Claire said. “We had some wonderful men, but women are different around men and we wanted a safe and a comfortable place for women.”

“We have a really diverse range of women who come to spend time with us,” Sister Claire wrote in 1987. “All of them live in the neighborhood, some with children, all in substandard housing, some in emergency housing provided by the county, some old, some young, all lacking most of the basic living skills except for survival. We provide the hospitality and warmth that the scriptures speak of – ‘a place of living water, new life.’”

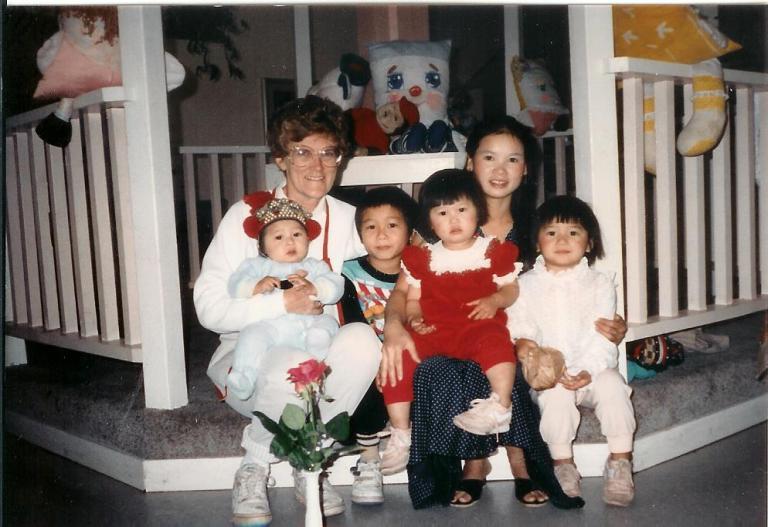

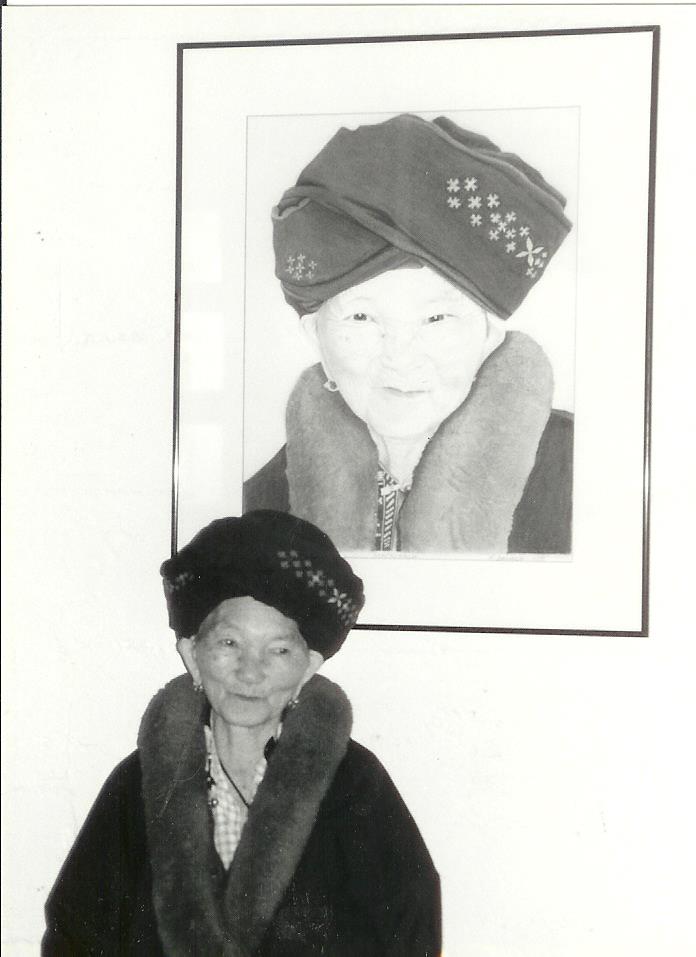

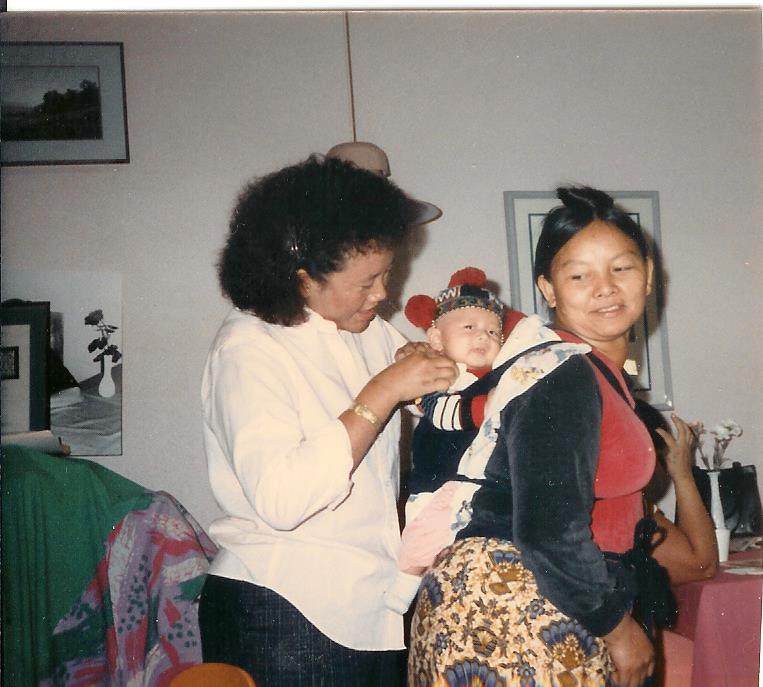

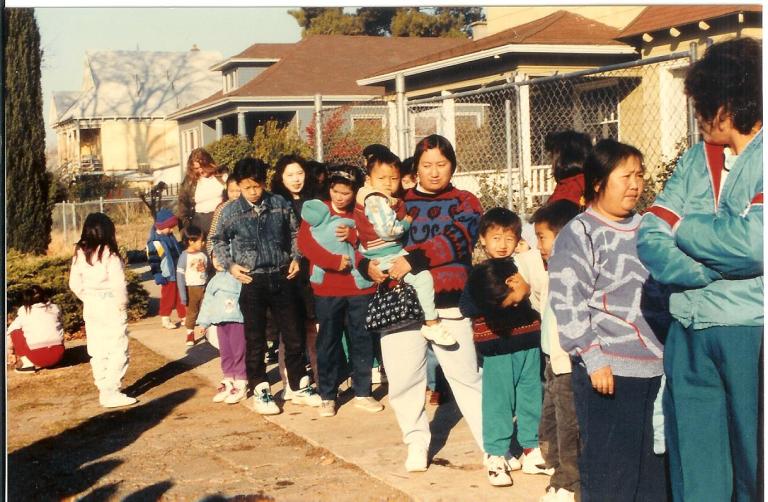

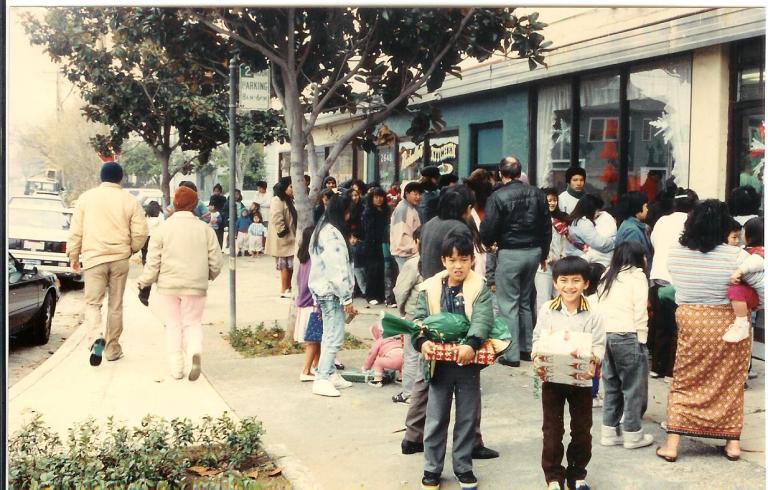

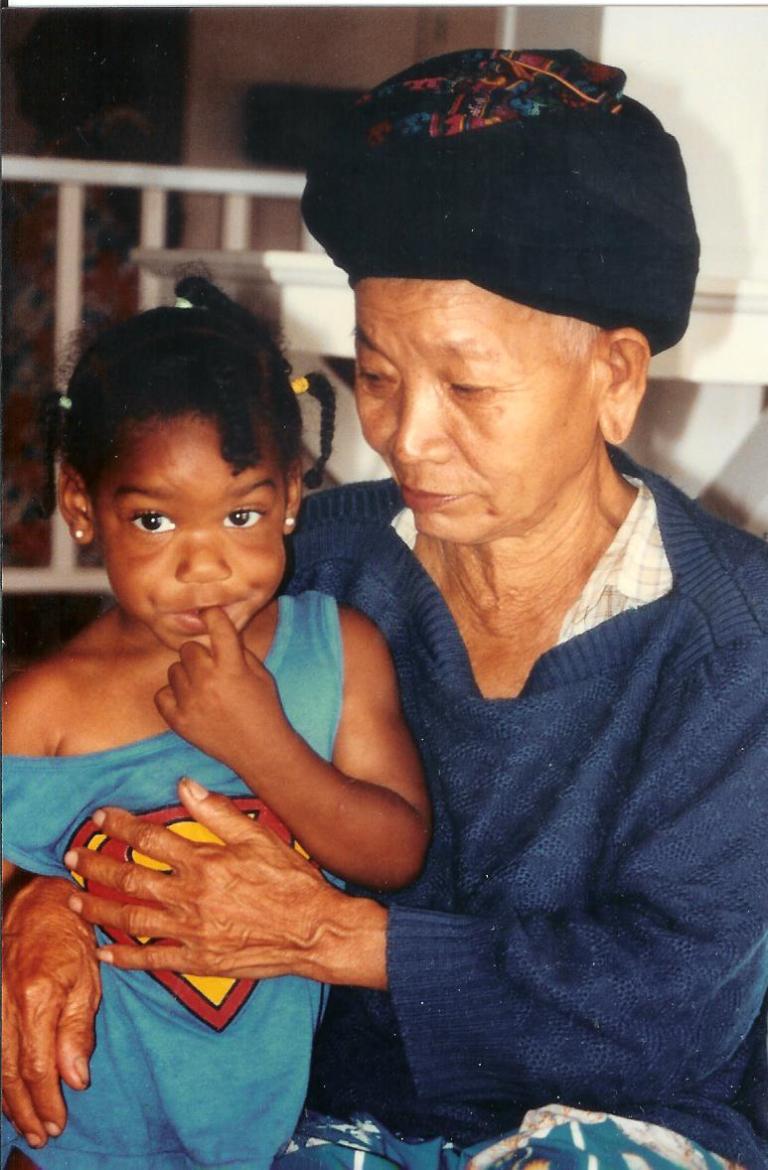

At first, the center mostly served African-American, Hispanic and caucasian women, despite the 10,000 refugees from Laos who settled in Sacramento after the Vietnam War ended in the mid-1970s. Many Mien refugees settled in Oak Park. The Southeast Asian ethnic group, who had lived in traditional farming communities in Laos, transitioned to refugee camps in Thailand before coming to the United States. The journey and the adjustment was difficult. Many in the community lapsed into poverty. They were left traumatized and also isolated from mental health care and social services because of their language barrier.

A friend of Sister Claire’s helped Wellspring connect with the neighborhood’s Mien community.

“Claire had a friend who had gotten to know some of the Mien community,” Sister Catherine said. “I said, ‘Claire why don’t you tell her to come?’ and I will never forget when I looked out the window and I said, ‘Oh my God, Claire look!’ The whole street was covered with Mien women and children.”

Sisters Catherine and Claire became students of Mien culture.

“We learned that the Mien are communal people,” Sister Claire said. “They share everything that they have. In America, we want bigger and better. In Laos, they had nothing so whatever they had, they took care of and grouped together. They would share any information that they got with the whole community so if someone said, ‘Well, Wellspring is here, they will help you if you go,’ everyone came to the Center.”

“We learned that [the Mien] had no written language until 1950 and that everything that they knew up until that point was handed down by word of mouth,” Sister Claire said.

Sister Catherine developed a close friendship with a young, Mien girl named Maye. Her parents were farmers who did not speak any English. Sister Catherine would talk to Maye for 10 minutes each night to strengthen her English. Now 38, Maye works in 34 countries as an expert on providing disaster relief to countries in the developing world. She credits Sister Catherine for teaching her about leadership.

“I remember when she was in high school and I said that she couldn’t realize her full potential in the public high school here, so I got $500 from Wellspring Women’s Center and went out to Loretto High School,” Sister Catherine said. “I told them, ‘This is all I have, would you educate her?’ And they did. So we have seen a lot of incredible successes that people have had because they have come here and it worked either through volunteers, Claire or myself. They were impacted by having someone teach them to look at their own potential.”

Sister Claire and Sister Catherine also were challenged to ease racial and cultural tensions among Wellspring’s guests when the Mien women were often picked on and targeted for ridicule.

“The poor seem threatened by immigrants,” Sister Claire said. “The blacks and the browns and the whites learned how to relate to the Mien through connection … Catherine and I worked really hard to integrate them.”

Their means of cultural acceptance? Breakfast chitchat and celebration.

“We always celebrated Mother’s Day and Christmas Day and we always invited whole families,” Sister Claire said.

In Wellspring’s early days, after the center closed at 11 a.m., Sisters Catherine and Claire would pick up doughnuts to serve the following morning and then visit guests in their homes.

“Being with our guests in their own environment was important,” Sister Claire said. “So what we would do is that we would go out, we would go visit people and help them organize their living space.”

“I assumed that all women knew how to clean houses [but] unless you have been taught how to clean a house, you don’t know how,” Sister Claire said. “So we would go into their houses and help them clean and organize. In this kind of neighborhood, the women had no place to wash clothes and they didn’t even have washing machines so one of the things that we learned was that they’d go to the Sacramento Food Bank and Family Services and get clothes, wear them until they couldn’t wear them anymore and then throw them in the closet. In those days, we had cloth diapers and the same thing would happen to those diapers. It was very unsanitary so we started giving out diapers and then someone said that we should collect soap and things like that – toothbrushes and toothpaste.”

Through this outreach, Wellspring’s Safety Net Services program was born. Now, guests can visit Wellspring’s backdoor and access hygiene items, birthday cards, reading glasses, sanitary pads, wet wipes and baby diapers among other necessities. In 2017, Wellspring gave out over 67,274 diapers, 32,319 tampons and pads and 4,650 bus passes.

“Our day seldom ends before 10 or 11 in the evening as there are meetings to attend, strategies to develop and needs to be met above the usual shop hours,” Sister Claire wrote in 1987.

Asked about boundaries between themselves and the guests, Sister Claire and Sister Catherine admitted that there were none.

“There were no boundaries,” Sister Claire said. “We did what we needed to do. I think it is the only way to be with people.”

“You can’t have such rigid boundaries and not be there for people,” Sister Catherine said.

“Another wise thing is that we never took money from government sources,” Sister Claire said.

“We didn’t want strings attached to us and maybe that is our fault,” she added. “Maybe, we are too arrogant.”

At Wellspring, women hardened by a lack of love and the despair of poverty have learned how to be with themselves and with each other.

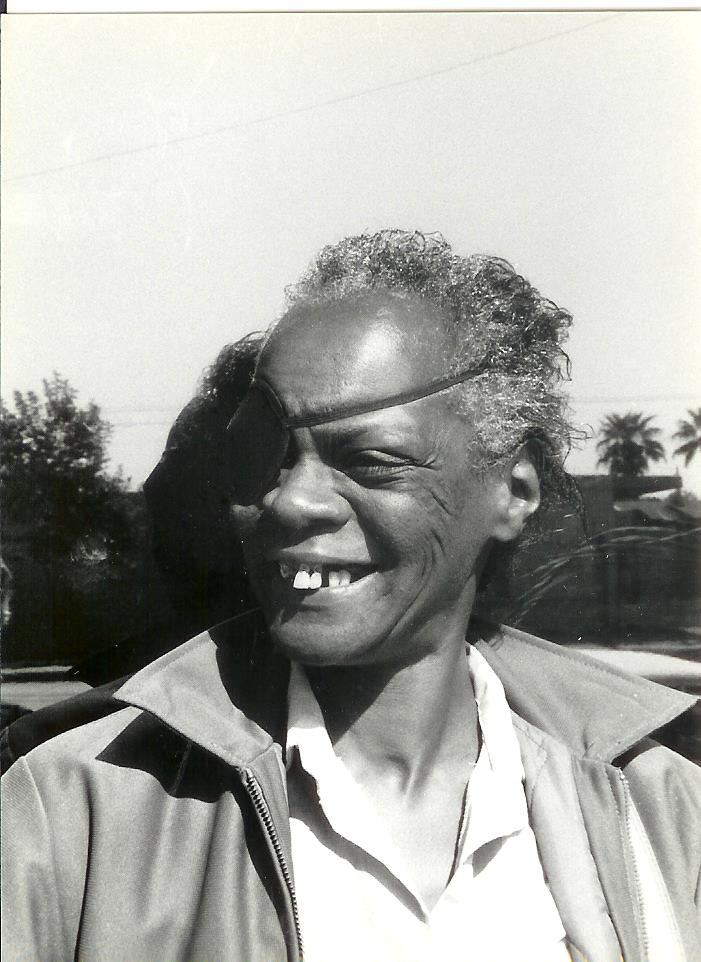

A guest named Susan was college educated. Raised in North Carolina, she came from an excellent background, but, ended up working up as a prostitute. One of the pimps who she was working for knocked out her teeth. Sister Claire and Sister Catherine found a dentist to fix her teeth.

“It made a world of difference to her life,” Sister Claire said. “She did remarkable things [after her teeth were fixed]. She went back to school and began to organize against the gangs in Oak Park that were just getting started.”

“Mildred McCaffrey [a volunteer] was probably 5-foot-1 and she wore 3-inch heels every day,” Sister Claire said. “She would come in dressed to the nines and one day she came into our second location pretty disheveled. We asked her what happened and she said that somebody just jumped her and had stolen her purse. Both Catherine and I were appalled … We said, ‘Excuse us, Mildred was just jumped by somebody and they stole her purse.’ With that, the room emptied out – Mien, white, black and brown. Twenty minutes later, they came back with her purse. They had broken the window of the person who had stolen her purse. I think that is empowerment.”

Margaret, an African American woman, was a string-bean. She told Sister Claire and Sister Catherine that she could make up to $1,000 a day standing on a street corner, selling drugs. She reported to the main drug dealer in Oak Park at the time, named Granny.

“Margaret taught me many lessons,” Sister Claire said.

Sister Claire ran into Margaret when Wellspring was closed for the month of July. Margaret said that hadn’t eaten in days and was out of cigarettes.

Sister Claire smoked at the time so she gave Margaret one of her cigarettes and they smoked in front of Wellspring. She bought her a pack of cigarettes and then took her to Kentucky Fried Chicken. Sister Claire left her purse in the car when she went into the fast food haunt to pick up Margaret’s meal.

After she said goodbye to Margaret, she looked in her purse and realized that Margaret had stolen $20 from her. She told Sister Catherine about the theft and then went to Granny’s house where they assumed Margaret would be spending her money. They wanted to confront Margaret.

Sister Claire walked up to Granny’s apartment and knocked on the door. Granny told her that Margaret had just left.

Sister Claire walked down the street and found Margaret. She asked her where her money was. Margaret said that she didn’t know where it was. Sister Claire told Margaret that she was very angry and then the two parted ways.

Margaret, an early-morning regular at Wellspring, didn’t come back to Wellspring for weeks, rattled and disgraced by her encounter with Sister Claire.

“Finally, one day, she went by the window and I said, ‘I’m gonna go get her,’” Sister Claire said. “And so I went and said, ‘Why don’t you come in for coffee?’ She said, ‘Because you and Catherine hate me.’ I said, ‘No one hates you, we love you. I don’t like you stealing money from me, but we don’t hate you so you better come back.”

Margaret continued coming to Wellspring for years and Wellspring became a site of forgiveness. When physical fights broil up in the center, guests may be asked to leave temporarily, but are always welcomed back.

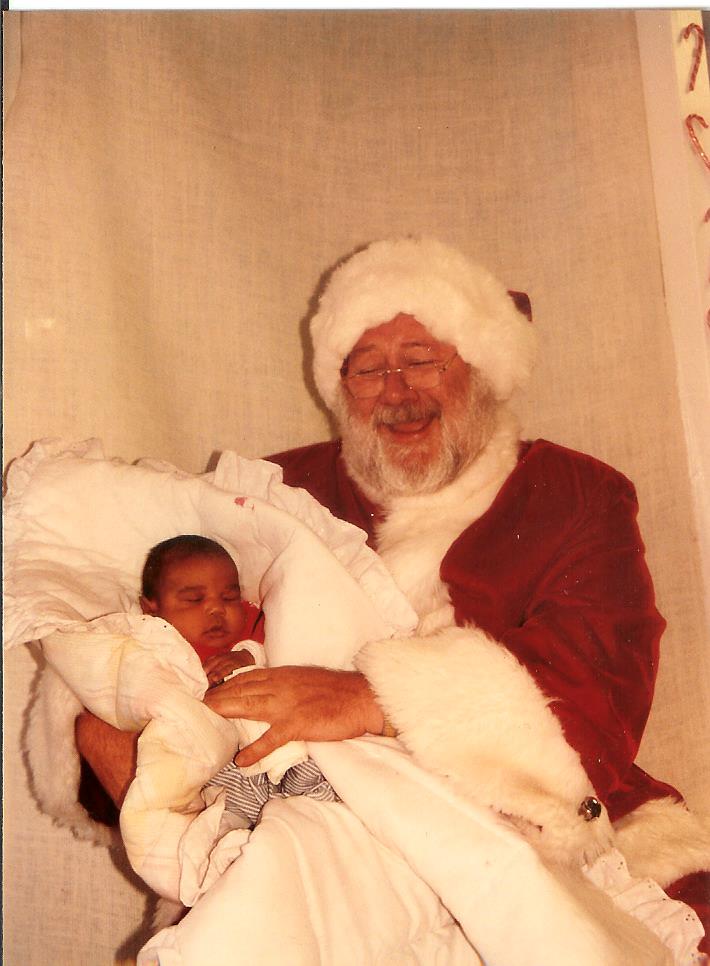

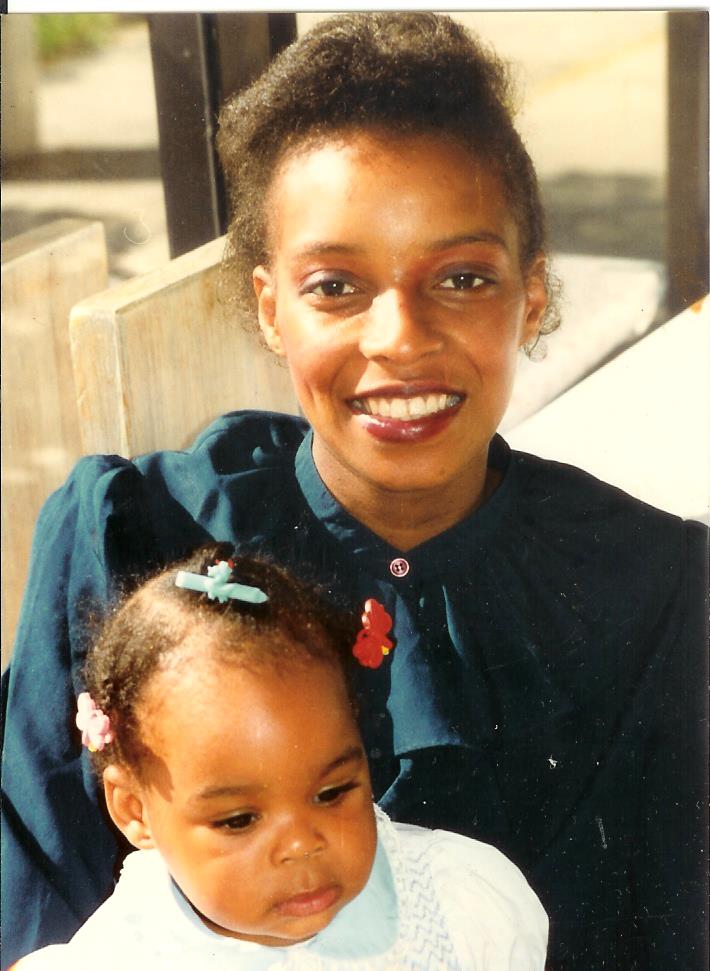

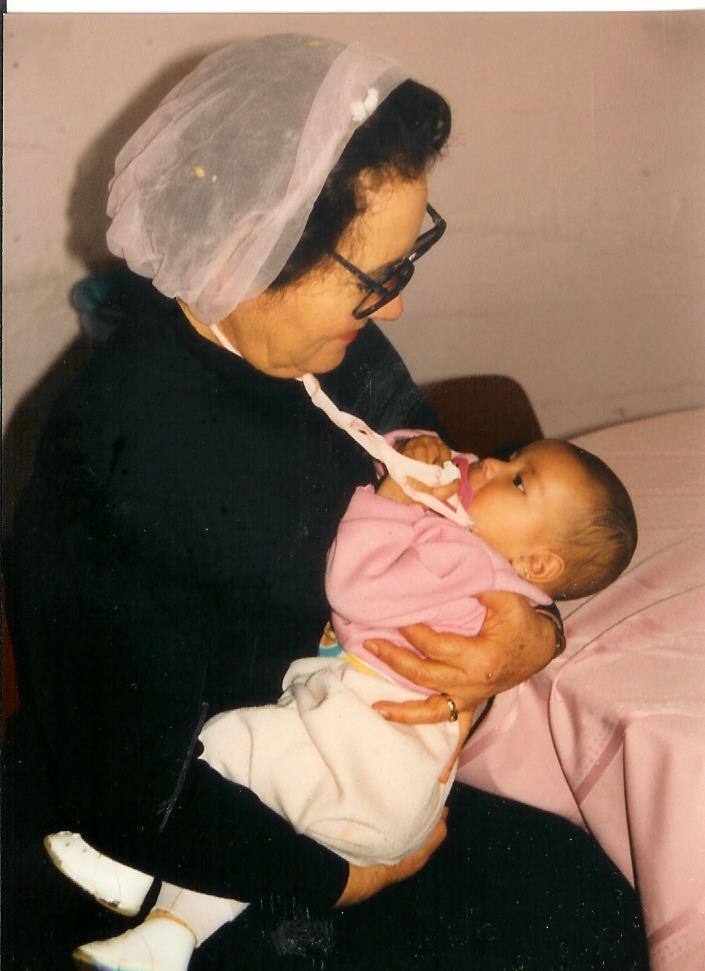

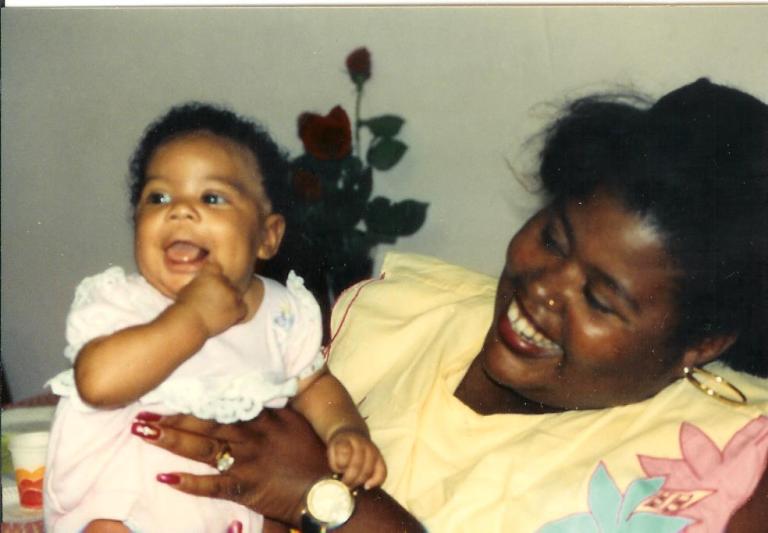

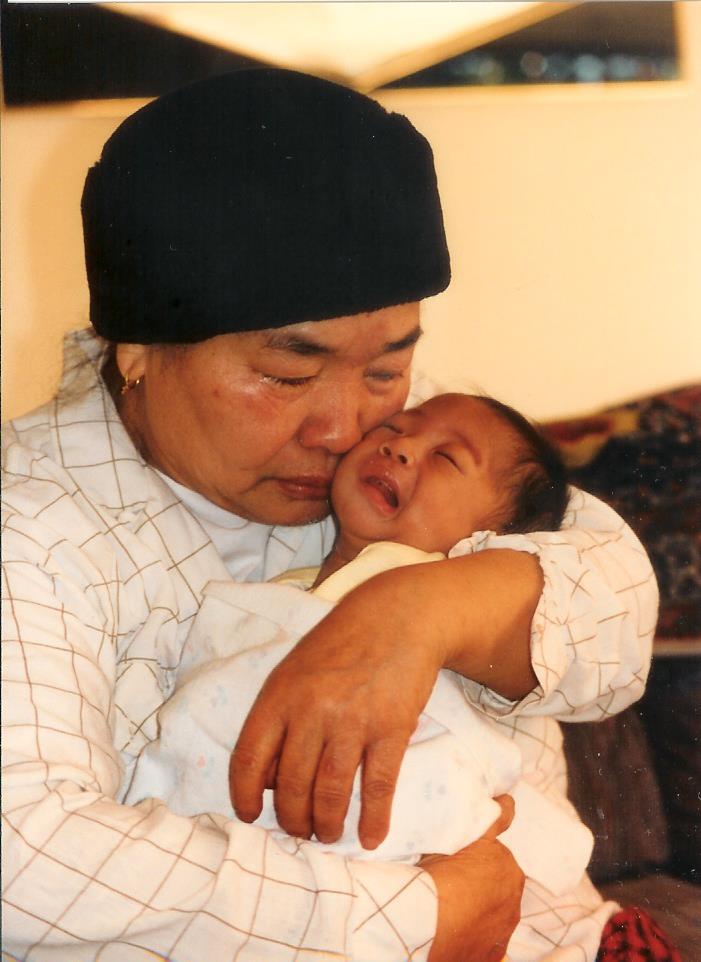

Motherhood also has been central to Wellspring’s mission.

“I had the privilege in working with some of the women to be invited to attend the birth of their babies,” Sister Catherine said. “That was a profound gift to be able to be present as a baby comes out, and for them, it was also a feeling of security – that they had someone that they knew with them in case something went wrong.’”

At the Children’s Corner, a preschool learning environment, children from two to eight interact with each other and volunteers. As a result, the children of Wellspring have grown up in community. At the same time, their mothers get a break from parenting and indulge in a supportive network of other women.

“It’s a beautiful thing because there is a sense of family here,” said Brianna, a guest. “A lot of people don’t have family. My son, Masaias, for instance, doesn’t have direct aunties or uncles in his life, but, here he has aunties and grandmas. If it wasn’t for this place, he wouldn’t have the village that it takes to raise a child.”

Wellspring gives out diapers every week.

“If it wasn’t for Wellspring, there would have been times when Masaias would have had to wear a diaper longer than he was supposed to,” Brianna said. “I always had fresh diapers for him and wipes. I wouldn’t have been able to afford them.”

Over the years, Wellspring has had three homes – its first location on 34th Street and Broadway, the second location on 33rd Street and Broadway and its current location in the Oak Park Historic Firehouse on 34th Street and 4th Avenue.

“We moved from 34th to 33rd Street just by picking everything up with the volunteers and walking everything down the street – the gazebo, the chairs etc.,” Sister Claire said.

When the second space on 33rd became too small, Sister Claire and Sister Catherine had to defend Wellspring’s plans to move to the historic Oak Park firehouse before the City Council.

“I wanted them to know that all the work that we were doing for Wellspring was for people who really needed it,” Sister Catherine said. “In the morning at Wellspring, we told all of the guests, ‘We want all of you mothers to bring your kids to this meeting.’ It was incredible and they came and they filled the whole room with the kids sitting on the floor. I said, ‘If they say no to us, they are going to have to look into the eyes of these children and mothers and see who they are saying no to.’ We got it passed.”

Wellspring’s current home is spacious and often bathed in light.

“We have a lot of sunlight in this building and I think that is very important …,” Genelle said about the firehouse. “If we were a little strip mall right here, it would feel different.”

Jean, the inspiration for Wellspring, visited multiple times and donated five dollars from her Social Security check to the Center.

And, nearly thirty years since its founding, Wellspring is still greeting newcomers. The staff has expanded from Sister Catherine and Sister Claire to include an Executive Director, Bilingual Outreach Coordinator, a Business Manager, a Women’s Wellness Coordinator, an Art of Being Coordinator, a Development Director, a Nutrition Services Manager and a host of 100 faithful volunteers.

Sister Catherine had to leave Wellspring when she incurred neuropathy and lymphedema after battling breast cancer – making it difficult to navigate the center’s steep staircase. She currently lives in Encino, California.

Sister Claire left Wellspring when she spiritually sensed that her time at the center was finished. After Wellspring, she worked for the Step Ministry at St. Francis of Assisi Parish – offering a place for homeless people to sleep on the Parish’s steps. Until she passed away in October of 2018, she worked as a spiritual director out of a small office in Midtown Sacramento on 21st Street.

“Rather than lifting me up, the experience of opening Wellspring has humbled me,” Sister Claire said.

“I think the most important part is that women are able to claim their dignity here,” Sister Claire said. “I think that all women have not been able to occupy their rightful place in the world, but I believe that poor women particularly have grown up in a world that generationally tells them that they are second class citizens. Wellspring doesn’t just change the women who come for coffee, it changes the volunteers who come to work with the people who are having coffee.”

“One of the most beautiful things is that Claire and I never felt like we had any sort of competition or rivalry,” Sister Catherine said. “We were open to one another. There were just so many things that were possible.”

“It changed my life,” Sister Claire said. “I think it changed Catherine’s life.”

“It’s amazing to think back that we created Wellspring, because neither of us had a clue,” she added.

Sister Claire believed that the creation of the center was guided by the Holy Spirit.

“I think for me, today, God is not a person,” she said. “God is an energy and that energy is love. Our job is to learn how to love, to receive love and to give love, and when we die, we return to love. I don’t know what all that means. I just know it in my heart and my head.”